| | By Ron Flatter

Special to ESPN.com

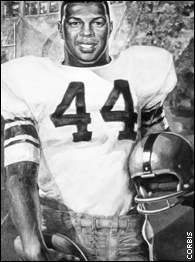

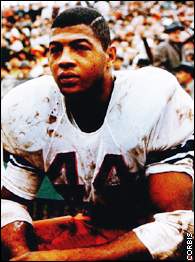

|  | | Davis was a two-time All-American at Syracuse. |

The honors came early and often, from the time he started with organized sports. Ernie Davis succeeded at every venue, a three-sport standout in high school, a two-time All-American halfback at Syracuse.

He led Elmira (N.Y.) Free Academy to a 52-game winning streak in basketball and as a Syracuse sophomore helped the Orangemen gain their only national football championship. As a senior in 1961, he became the first African-American to receive the Heisman Trophy and was the No. 1 pick in the NFL draft.

And then, stunningly, he was gone. Struck down by leukemia, Davis never realized his dream of playing in the NFL.

In March 1963, while in remission, Davis wrote an article for The

Saturday Evening Post in which he said, "Some people say I am unlucky. I don't believe it. And I don't want to sound as if I am particularly brave or unusual. Sometimes I still get down, and sometimes I feel sorry for myself. Nobody is just one thing all the time.

"But when I look back I can't call myself unlucky. My 23rd birthday was December 14. In these years I have had more than most people get in a lifetime."

Two months later, Davis died.

Davis was a coach's dream: modest, hard working, team-oriented, a sportsman who never put down opponents or teammates. "An excellent practice player. He lapped everyone," said John Mackey, a Syracuse teammate who later starred in the NFL.

Davis never took himself that seriously. He was quiet, a stutterer as a child who improved his speech as demands on his public speaking increased. He remained appreciative of those who helped him on the road to fame.

Friends noticed. Ben Schwartzwalder, his football coach at Syracuse, said, "I never met another human being as good as Ernie."

Davis was born on Dec. 14, 1939, in New Salem, Pa. His parents separated shortly after his birth, and his father was soon killed in an accident. He grew up in poverty in Uniontown, a coal-mining town 50 miles south of Pittsburgh, where he was raised by caring grandparents.

At 12, Davis moved to live with his mother and stepfather in Elmira. A high school All-American in football and basketball, he won 11 letters at Elmira Free Academy. Of the three sports he played, he thought he was weakest in baseball, though a scout once predicted that with some refinements in his swing, Davis could become a major leaguer.

The growing media attention never changed him. "Ernie was the same kid at the end he was at the start," said Jim Flynn, his high school basketball coach.

More than 30 colleges, including UCLA and Notre Dame, recruited Davis

for football, but Syracuse, just 90 miles away, held an advantage. Syracuse also had a famous player in its corner, Jim Brown, the first in a line of star running backs with the Orangemen.

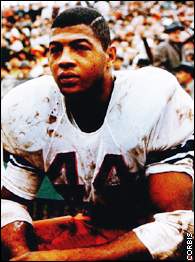

|  | | Davis rushed for 2,386 yards and scored 220 points for the Orangemen. |

"I wanted to play in the big time," Davis said after leaving Syracuse, "and a lot of people, including Jim Brown, persuaded me that I'd have better opportunities there."

Davis didn't disappoint in Syracuse. The only black player on the freshman team, he led the squad to its first unbeaten season, then became the varsity's top rusher as a sophomore in 1959. With colleges still playing one-platoon football (Davis played defensive back as well as halfback), Syracuse assembled a dominant team. The Orange outscored opponents 390-59 in its 10-0 regular season before gaining its first bowl victory.

Dubbed the "next Jim Brown," the 6-foot-1, 205-pound Davis wore Brown's No. 44. He ran for 686 yards in the regular season, averaging seven yards a carry, and scored 10 touchdowns (eight rushing). Against West Virginia, he ran for 141 yards on nine carries, setting a school record for per-carry average, 15.7, and scoring twice.

In Syracuse's 23-14 victory over Texas in the Cotton Bowl that clinched the national title, Davis, despite playing with a hamstring pull, scored two touchdowns, one on a bowl-record 87-yard reception, and was selected the game's Most Valuable Player. Just before halftime there was a bench-clearing brawl with racial overtones. Syracuse linemen contended that a Texas lineman delivered a racial slur to John Brown, a black Syracuse player, igniting the fight.

Davis was to have received his MVP award at the awards banquet that night. But when bowl officials said that only white players were invited to the dinner and that Davis would have to leave after picking up his trophy, the Syracuse team refused to attend the affair.

Before his junior year, Davis was chosen a preseason All-American by Playboy magazine, whose sports editor Anson Mount later called him the "greatest running back who ever lived up to that time."

The 1960 season began with an 80-yard Davis touchdown run on the first play from scrimmage against Boston University. "Those blockers wiped everyone out," Davis said. "A little kid could have run that one."

Syracuse won its first five games, then was upset by Pittsburgh 10-0, ending its 22-game regular-season winning streak. The Orange fell to Army the next week and finished the season 7-2 and without a bowl bid.

Davis was the nation's third-leading rusher, running for 877 yards and a

school-record 7.8 yards per carry as he was voted an All-American.

The Orangemen went a disappointing 7-3 in the 1961 regular season, but Davis ran for 823 yards as he averaged "only" 5.5 yards a carry and scored 94 points. He completed his career by rushing for 140 yards and scoring a touchdown in Syracuse's 15-14 victory over Miami (Fla.) in the Liberty Bowl.

His career 2,386 rushing yards and 220 points broke Brown's school records.

"He's the kind of runner you hate to coach against," Penn State coach Joe Paterno said. "You can't instruct a boy to tackle a man if he can't catch him."

An All-American again, Davis beat out Ohio State's Bob Ferguson and

Texas' Jimmy Saxton for college football's most prestigious award. "Winning the Heisman Trophy is something you just dream about," Davis said. "You never think it could happen to you."

|  | | Davis met President John Kennedy while in New York to accept the Heisman Trophy. |

When he was in New York to receive the Heisman, Davis met President John Kennedy, a short visit that thrilled him. "Imagine," Davis said, "a president wanting to shake hands with me."

The Washington Redskins made Davis the first pick in the NFL draft on Dec. 4, 1961, but soon traded him to the Cleveland Browns, who signed him to the largest contract up to that time for a rookie - three years for $65,000 plus a $15,000 bonus.

The next July, while training with the College All-Stars for their game

against the NFL champion Green Bay Packers, Davis awoke one morning with swelling in his neck. A trainer sent him to the hospital, and doctors soon discovered the leukemia.

They told Davis he had a blood disorder, but didn't tell him it was leukemia until October, after he had been in and out of the hospital. "Either you fight or you give up," Davis said in recalling how he felt when told the news. "For a time I was so despondent I would just lie there, not even wanting to move. One day I got hold of myself. I decided I would face up to whatever I had and try to beat it."

At that point, the disease was in remission, his blood count was normal and Davis kept planning for pro football. He practiced with the Browns, though often by himself on the sidelines, and said he felt strong. However, coach Paul Brown, heeding the advice of medical people who warned him of the risks, did not play Davis.

Sitting out frustrated Davis, who said he wasn't in pain. The next spring, Davis noticed more swelling and entered the hospital again. Two days later, on May 18, he died in his sleep.

His tombstone reads: Ernie Davis / 1961 Heisman Trophy / 1939-1963.

| |

ALSO SEE

More Info on Ernie Davis

AUDIO/VIDEO

Art Modell on Ernie Davis Art Modell on Ernie Davis

avi: 810 k

RealVideo: 56.6 | ISDN | T1

John Mackey on Ernie Davis. John Mackey on Ernie Davis.

avi: 836 k

RealVideo: 56.6 | ISDN | T1

SportsCentury on Ernie Davis. SportsCentury on Ernie Davis.

wav: 294 k

RealAudio: 14.4 | 28.8 | 56.6

|

Art Modell on Ernie Davis

Art Modell on Ernie Davis John Mackey on Ernie Davis.

John Mackey on Ernie Davis.

SportsCentury on Ernie Davis.

SportsCentury on Ernie Davis.