|

|

| Tuesday, June 8 The new kids in town By Rob Gloster Associated Press |

|||||||||

|

SACRAMENTO, Calif. -- In many ways, Yolanda Griffith is starting over again.

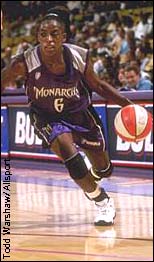

The 29-year-old forward has an "R" next to her name on the training camp roster of the Sacramento Monarchs, the WNBA team that selected her after the American Basketball League went broke. As in rookie. "I have to adjust to the smaller ball, to the new rules, a new team," Griffith said after an afternoon practice with her third team in three seasons. "It's going to be an adjustment, not just for me but all the WNBA players and the ABL players coming in, too." Griffith was the first player selected in the ABL draft in 1997. She was runner-up for league MVP her first year, and averaged 18.4 points a game in two ABL seasons. But her first team folded, and then the league went bankrupt. Griffith, who also played professionally in Germany, was one of dozens of players left jobless last December, midway through the ABL's third season. The ABL lured top players with big salaries -- about double those of the WNBA -- but could not attract enough TV or sponsorship interest to survive. The league's demise left a huge pool of talent looking for work. The WNBA allowed each team to add three ABL players to its roster, while expansion franchises Minnesota and Orlando got to select five of the players each. The result was that 35 of the 50 players selected in the WNBA draft in May were from the rival league. The merger should improve the level of play in the WNBA, but it has left many ABL players on the sideline and will do the same to some WNBA veterans when final cuts are made before the WNBA's third season opens on June 10. "I think a lot of the WNBA players on the borderline are afraid they'll lose their jobs," said Sacramento's Ruthie Bolton-Holifield, who has averaged 17.9 points a game in two seasons with the Monarchs. "If we hadn't had a limit, we would probably have five ABL players on each team. I'm sure a lot of the WNBA players resent it because they may lose their jobs. "I have some teammates who didn't make it back here," she added. "They don't resent the ABL players. They think the league wasn't fair to have the ABL players come in this season and take their jobs. The WNBA players feel like we sacrificed to go to a league that paid less, so the league should have showed some loyalty." Some ABL stars will be watching women's basketball on TV this summer. Venus Lacey, a member of the 1996 U.S. Olympic team, played for three teams in three seasons with the ABL. Now, having finished up her sociology degree at Louisiana Tech, she's in Ruston, La., looking for a job as a high school teacher and coach. She'll start working on her master's degree this summer. "It's a loss because we have a lot of people out of a job," she said. "But life don't stop there, it goes on. You moan a little bit and then you go on. I have a life even though it isn't playing basketball. To be honest, I always wanted to finish up my degree." Beverly Williams helped Griffith lead the Long Beach StingRays to the ABL finals in her first year. When the league disbanded the Long Beach team, she ended up with the Columbus Quest, which won the league's only two championships. Now Williams is working out in Austin, Texas, while helping kids at the city's parks and recreation department. She hopes to play for a team in Europe -- perhaps Greece -- starting in August, and will try again to land a WNBA spot when the league expands next season. "Once the WNBA games start, I'll want to be a part of it, and I can't," she said. "It's very disappointing." Maura McHugh, who coached the StingRays and then was the director of player personnel for the ABL, is now an assistant coach with the Monarchs. She said the leagues have different playing styles. "Overall, the ABL was a a faster game and a little bit more physical," McHugh said. "The refs won't allow that here. That's one thing a lot of the ABL players are going to have to get used to." Former ABL players such as Griffith also must adjust to what she called "a big pay cut" -- the average salary in the ABL's abbreviated third season was about $90,000, while the average WNBA salary last season was about $47,000. And the ball is different. The WNBA uses a women's college basketball, while the ABL used the larger ball of international competition. Kate Starbird, who averaged 12.9 points a game in two seasons with Seattle of the ABL, is another Monarchs player with an "R" next to her name. "I feel confident the real rookie year is behind me. On the court I'm not a rookie, though off the court a lot of things are new," she said outside the Monarchs locker room at Sacramento's Arco Arena. "Today I got lost trying to find the weight room." |

|

||||||||