| ||||||||||||

| ALSO SEE Tampa Bay at St. Louis  War Room preview: Bucs at Rams War Room preview: Bucs at Rams | ||||

| ESPN.com NFL | ||||

Wednesday, January 19

Old coach learns new tricks

Special to ESPN.com

I like Dick Vermeil. I like Dick Vermeil because he's old. I like him because he is old and he once quit football. I like him because he quit football and then came back.

I like Vermeil because he figured out how to come back without going insane.

| |

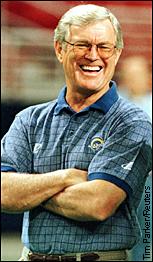

| The Vermeil of '99 is a far cry from the one we saw even last season. |

And that is a lie, of course. Dick Vermeil, the coach of a St. Louis Rams football team that has gone from 4-12 a season ago to hosting the NFC championship on Sunday in the Airline Dome, is only 63 years old. In America these days, that's barely middle age.

Vermeil looks great, acts healthy and still has the constitution to be a full-time head coach, which is a great job as long as you're fond of 168-hour work weeks. He has the enthusiasm of a kid and the ability to cry on demand of a Jennifer Love Hewitt, and he very basically knows what the heck he's doing out there.

But in the NFL, 63 is either the number of a fat offensive lineman or an age to which almost no one in any actual employee capacity can relate. Put it this way: Dick Vermeil has socks older than some of his players. I'm not saying they're fundamentally immoral socks, I'm saying 63 is 63.

And that is why I like Vermeil.

They talk in football about players turning their careers around, but not even Jeff George can match what Dick Vermeil has done over the past couple of seasons. This is a man, remember, who retired from coaching nearly two decades ago because he was so insistently intense -- because he was a Roman Candle firing out of both ends -- that he developed one of the first modern cases of sports burnout.

And this is a man, remember, whose own players as recently as last season were threatening a team-wide mutiny over Vermeil's over-the-top practice schedule, the long, drawn-out and pointlessly physical sessions that some of the best Rams believed were draining the life out of them before Sunday ever arrived.

So it was that Vermeil hit this season as an old-guy coaching suspect, right there alongside such veteran recyclables as the Lions' Bobby Ross, the Colts' Jim Mora and the Saints' Mike Ditka. It was Vermeil's third season in St. Louis, with just nothing to show for Seasons 1 and 2. The word on the street was that the Rams had made a significant miscalculation in their judgment that Vermeil still had something to offer the modern player.

Ever so wrong, as it turns out. The Rams love Vermeil; they have thrived upon his emotion and his stout belief in them; and they have rallied around a heretofore unproven quarterback to push to within a victory of the Super Bowl.

But before the Rams could switch over to the Vermeil side of the fence, the coach himself had some changing to do -- and this is the part of his story that Vermeil is the most reluctant to acknowledge. He'll say that he is basically the same person he always was, wearing his heart on his sleeve and all that -- and you couldn't disprove it if you tried.

But Vermeil changed in other ways. At 63, with a veritable lifetime of coaching behind him, he had to find new ways to get across his established ideas. He had to listen to his players and trust them, and regardless of age, that is one of the most difficult leaps of faith for any coach to make.

The Rams wanted shorter practices; Vermeil gave in. They wanted less full-pad contact during the week; Vermeil gave in. He incorporated more player ideas than he ever has before, and when Trent Green went down with injury, the coach threw untested quarterback Kurt Warner out there and told him that he would be the QB to stay -- never seriously considered making a move outside the organization.

It sounds like basic stuff, the normal you-scratch-my-back, I'll-scratch-yours currency of the NFL. It wasn't basic in the least. It required Dick Vermeil to switch things up, and that is why it's all the more encouraging that it played out the way it did.

Bobby Ross in Detroit, the same. You can knock the Lions for their dismal flame-out at season's end, but the fact is, they got to 8-4 at one point in the season without Barry Sanders carrying the ball once; and they did so, in large measure, because Ross took a hard look at himself last off-season and decided he was going to have to change as a coach, become less negative, more accessible, more willing to incorporate player feedback and the like.

It was asking an old dog to learn new tricks. Ross learned. Dick Vermeil learned. It's an encouraging thing almost any way you look at it. And even if it's the thing Vermeil would least like to discuss, it is what makes the man so completely appealing as a story just now. You don't have to be 63 to see that.

Scouting around

Two questions: One, why should anyone care what John Rocker says in the first place?, and two, how long before he stops saying it? Of all the problems facing Major League Baseball in this arena -- and let's go with the lack of diversity in front offices, the Tomahawk Chop and Chief Wahoo, just to start the list -- John Rocker is the least of them. He can't hire, fire, promote or punish. And he's a closer, which means he'll be out of the game in a couple of years. The man doesn't rate. Simple as that.

Gossage also arrived on the scene before the advent of the Dennis Eckersley type of save, where the closer might work only one or two batters to earn the statistic. But don't let the numbers deceive: For years and years, the Goose was It. It took Tony Perez nine tries to get to Cooperstown; if sheer dominance is a criterion, perhaps we'll see Gossage yet.

Mark Kreidler is a columnist for the Sacramento Bee, which has a web site at http://www.sacbee.com/.

|

ESPN INSIDER

Copyright 1995-2000 ESPN/Starwave Partners d/b/a ESPN Internet Ventures. All rights reserved. Do not duplicate or redistribute in any form. ESPN.com Privacy Policy. Use of this site signifies your agreement to the Terms of Service. | ||||