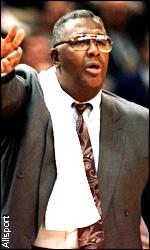

| | When Georgetown University won the NCAA men's basketball championship in 1984, head coach John Thompson made history. Thompson, though, had mixed feelings about becoming the first African American coach to win a national title in college basketball.

|  | | John Thompson's Hoyas won the 1984 NCAA title. |

"I might have been the first black person who was provided with an opportunity to compete for this prize, that you have discriminated against thousands of my ancestors to deny them this opportunity," Thompson told Gary Miller on a recent edition of ESPN's Up Close. "So, I felt obligated to define that, and I got a little criticism for saying it..."

Thompson, currently working as an NBA analyst for TNT, appeared on Up Close to help celebrate Black History Month. The former Hoya coach also touched on his personal experience with discrimination. An edited transcript of Thompson's Feb. 14 comments follows.

Miller: Take me back to the first time that you recall being involved in a racial incident that you remember to this day in your personal life...

Thompson: I think my complexion, I am a black African-American, and I think blacks had been taught, Gary, to dislike themselves. And the first form of discrimination that I ever encountered was blacks against blacks, because I didn't encounter whites when I was very young. I lived in public housing, and then I moved to Northwestern Washington, D.C., which was pretty much exclusively black. So blacks, when trying to meet the standard of approval, thought that to be fair-skinned or light-skinned was acceptable, but society had taught them that. So look at me (laughs). So, to encounter black against black, people can teach you to dislike yourself and that's what I remember the most.

Miller: So you encountered initially more discrimination within your own race of shades...

Thompson: Far more...far more within my own race as a young person. Until I got older, I had to go to high school before I really encountered whites, and got pretty much into a white setting, but most of the racial discrimination that was inflicted upon me was blacks against blacks.

Miller: Was there an incident that sticks with you or that really affected you to this day?

Thompson: There were a whole lot of them (laughs). There were a whole lot of them. I don't think there was any one. The first time I can probably ever remember dealing with a white person with something that was discriminatory is, I remember going into a drug store and I asked for vanilla ice cream, and the lady made a crack to me about, "y'all don't want chocolate ice cream?" I was trying to digest that, but most of the things that occur in your life, particularly when you're young, are small stupid things, but very much piercing and offensive and hurting.

Miller: You're the very first African-American head coach to win the national championship in college basketball. What do you think of that label?

Thompson: Well, I was very proud of winning the national championship and I was very proud of the fact that I was a black American, but I didn't like it if the statement implied that I was the first black person who had intelligence enough to win the national championship. I thought it had to be defined, and a lot of people will come up to you and say, "well, how does it feel for you to be the first African-American to win the national championship at the Division I level," and I said I feel offended by the statement, because the statement implies that John Thompson was the first black person who had enough intelligence. I might have been the first black person who was provided with an opportunity to compete for this prize, that you have discriminated against thousands of my ancestors to deny them this opportunity. So, I felt obligated to define that, and I got a little criticism for saying it, because some young guy came up to me and asked me, "How does it feel, coach Thompson, to be the first African-American...," and I said "I feel offended by the fact of what you're saying." But, I explained to him because a lot of men were deprived of the opportunity, who would have won it far before I did.

Miller: Well it changed your profile completely. You went to three Final Fours in a span of four years there, and you became one of the giants in college basketball. In 1989, with this profile pronounced, you walked off the court and protested a BC game and within a year you get Prop 42 changed (a rule restricting freshman eligibility).

Thompson: Well, the thing that I felt is that this was happening and you were putting in this legislation that would inhibit a lot of young kids from having an opportunity to become doctors, lawyers or whatever else they wanted to be, not just basketball players. Basketball has never been just about basketball. It's a stupid game if it's just about basketball... You've got a lot of people running around in shorts throwing the ball in the goal. I hope I see things a little bigger. But, that stupid game has provided a lot of opportunities, and now you go make this legislation, and you deprive a lot of kids from coming through the only tunnel that they might have of getting into the world of work or getting into the world of opportunity, so I resented that and it was being done very quietly. Very few people said anything about it or nothing was made out of it, and a lot of things that have hurt us you haven't heard a bugle blowing, they've happened very subtly. So, I felt a little bit obligated at that point in time to say, "look what is going on, that this is one of the few avenues that we have an opportunity to express ourselves enough so that we can expose ourselves to enough education so that our kids can be better."

Miller: When you came to Georgetown in '72, the basketball team was basically all white. Over the years, it changed shades and became almost an all black team for much of your time. What reaction did you get initially as that complexion of the team started to change?

Thompson: I think I got some reaction, but I didn't pay attention to a lot of people's opinion, or I wouldn't have ever taken the job. I think again, interestingly enough, Gary, more blacks expressed to me a concern about the complexion of my team. Whites probably expressed that concern to whites and to the newspapers, but blacks being taught again to be afraid of their own or being reluctant to see something that was turning black? I didn't choose blacks to make a racial statement, black kids played basketball well. If I were running a hockey team, I would have had an all-white team, or if I had a volleyball team, I would have had an all-white team, but I was not afraid of blacks to the extent that I discriminated against them, and that's where I had a problem. People thought that I was discriminating against whites. In fact, what I was doing is not discriminating against blacks, because I remember when I went into the NBA, you weren't competing for 11 spots, you were competing to find out how many blacks they would keep. So, it was not a question of you trying to make 11 spots on the team, because black kids played it, because it was accessible to them, because it was a means by which they could get recognition. So, my having a predominantly black team had more to do with me being fair than me discriminating against anybody.

Miller: Some of the guys you sent into the NBA were there when you retired at Georgetown: (Alonzo) Mourning, (Patrick) Ewing, Allen Iverson being the latest one, Dikembe Mutombo, a long list of guys. Do you feel that Allen Iverson, who has now made a real splash at the All-Star game, who is one of most popular players in the league, has a sense of history of what went before him, and do you think he should?

Thompson: I think he has a sense of history. You'd have a sense of history if somebody incarcerated you and you stayed in jail for something you should not have been put in for. If you look at the state of athletics today, this young man served prison time, there was not a knife or a gun involved in a bowling alley brawl, and he did time for it. Now, you can't have a brawl without an automatic weapon involved, but Allen Iverson did time. I would say that he has a greater sense of history than John Thompson! I have never been incarcerated, but that was an unfair act regardless of what he did at that point and at that time. Obviously, he has been excused of it and he's accepted it, but he still is a young man. He should enjoy himself and enjoy his life, but at the same time, as I indicated with Michael (Jordan) and as I indicated with Magic (Johnson) entering into the business world, unfortunately they do not have the luxury of just being Magic and just being Michael. They are carrying the burden for a lot of people, they are clearing a path for a lot of people because, fair or unfair, the success of those people will have an influence on how others will be able to have an opportunity.

Miller: One of the things that he (Iverson) gets criticized for, and as you say it's not fair, but when you get to that prominence and when you get a contract like that, when he gets on your TNT broadcasts on a regular basis because of the way he plays, people scrutinize his life and they talk a lot about his posse. Were there any roots of that when he was at Georgetown, did he have hangers-on...

Thompson: No, he didn't. I don't play that. I don't have posses. I'm the one who has the posse (laughs). Allen didn't have any posses around me, but you've got to understand, things in that kind of world, and I find if difficult for people to accept, Gary, the fact that in their minds, or to not accept, why does this young man have a posse? A lot of aspects of society he was not permitted to enter into. We still now are fighting to make certain that if a young man goes to most of the major universities in the United States, that they'll employ them as something other than a coach. It used to be something other than a player. Now we are arguing and debating, the National Coaches Association, which happens to be white and black, came out and protested about two or three weeks ago that the kids who participate in the NCAA can get jobs who are of color. Now, why would Allen Iverson not have a posse? They love him, they're around him, they're comfortable with him, they include him. He doesn't have to score 40 points to be included into their world. So, people amaze me when they say, "Why did he hang with this person?" He hangs with them because those are the people who saved his life, those are the people that walked with him before he scored 40. Now, he has to use some discretion and learn to separate them, but it's ignorance on the part of society that has not accepted a person to wonder why they like the people that did accept them all their lives. I call that loyalty. He's got to be smart enough to know that I'm moving out, what they're saying is that now that we have let you into our world, you score 40 points, you get millions of dollars, tell all those people who loved you to get the hell away from you. That's ridiculous.

| |

|